The Crisis of the SPD: Where Now for Germany’s Social Democrats?

Published:

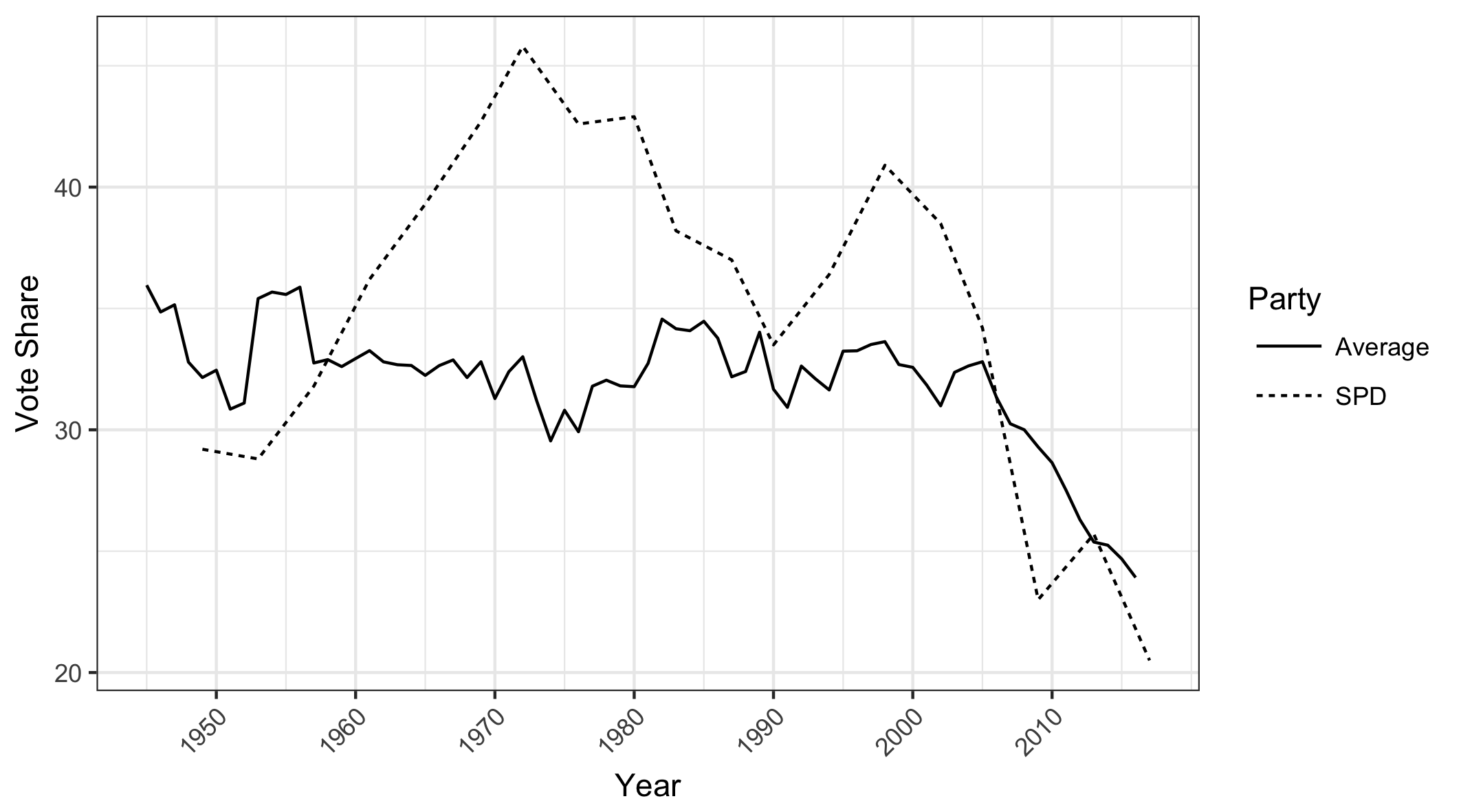

The German SPD hit a historic low in the 2017 federal elections. The 20.5 per cent of votes received was the party’s worst result since the Second World War. On the evening of the election, Martin Schulz called the result a “bitter defeat”, which was still something of an understatement. Despite the short revival of the SPD in the polls at the beginning of the year, the party was defeated for the fourth Bundestag election in a row. When compared to 1998, when Gerhard Schröder won 40.9 per cent, the party’s vote share has nearly halved over the last two decades. The party has now been thrown into a deep and existential crisis.

But this crisis is not unique to Germany. Since the mid-2000s, almost all social democratic parties across Europe have struggled and they are now falling like dominoes. In 2017 alone, the Dutch Labour party and the French Socialists have experienced electoral obliteration and the Austrian SPÖ is expected to lose upcoming elections in October. There are only very few social democratic parties in Western Europe which are resisting this trend, including the Socialist Party in Portugal and the British Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn.

Figure 1: The SPD’s vote share compared to the average vote share of social democratic parties in Western Europe (1945-2017)

Source: ParlGov Database 2016, author’s update and calculations

In Germany, the reasons for the decline of the SPD are, of course, multi-faceted. In the latest elections, the social democrats lost voters to parties on the left and right and it will not be easy to win all of them back. However, a few points stand out that explain the SPD’s plight. First, governing has been costly for the SPD. The SPD has been in power for fifteen out of the last nineteen years and it was punished at every election after it had been in government. Under Gerhard Schröder, the centre-left government implemented liberal labour market reforms and retrenched the welfare state. As a result, many traditional social democratic voters have turned away from the SPD, contributing to the rise of the far left party Die Linke.

Afterwards, the SPD joined Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU in government in two grand coalitions, first in in 2005 and then in 2013. This helped the SPD to steer Germany through the financial crisis during the first grand coalition and allowed them to implement several pet projects (including the introduction of a national minimum wage) during the second. Still, both grand coalitions had devastating electoral consequences for the SPD: in 2009, the party lost 11.2 percentage points and dropped to 23 per cent; and in 2017, the party lost 5.2 percentage points and dropped even further.

On both occasions, the grand coalition created a strategic dilemma for the SPD during the campaign: while it tried to criticise Merkel, the party also sought to praise its own achievements in government. As a result, the SPD was unable to set out a clear alternative to Merkel’s leadership and lost many voters who were disappointed with the status quo. Even Martin Schulz, who had not been part of the grand coalition, was unable to draw a clear distinction between the two mainstream parties and seemed reluctant to launch a full-frontal attack on Merkel during the campaign.

The second factor contributing to the SPD’s weakness was the party’s inability to connect with crucial parts of the electorate. Importantly, the SPD lost a lot of support among the working class, its traditional core clientele. In the 2017 election, only 24 per cent of all workers voted for the SPD according to the exit poll, while 25 per cent voted for the CDU/CSU and 21 per cent voted for the AfD. The results indicate that the party has lost touch with the working class, undermining a central promise of the SPD: to build a bridge between workers and left-leaning social professionals, uniting them under the umbrella of a single political project. Instead, the SPD has largely become a middle-class party. As such it was always going to be difficult to win elections against Merkel, who has firmly and successfully anchored the CDU/CSU in the centre.

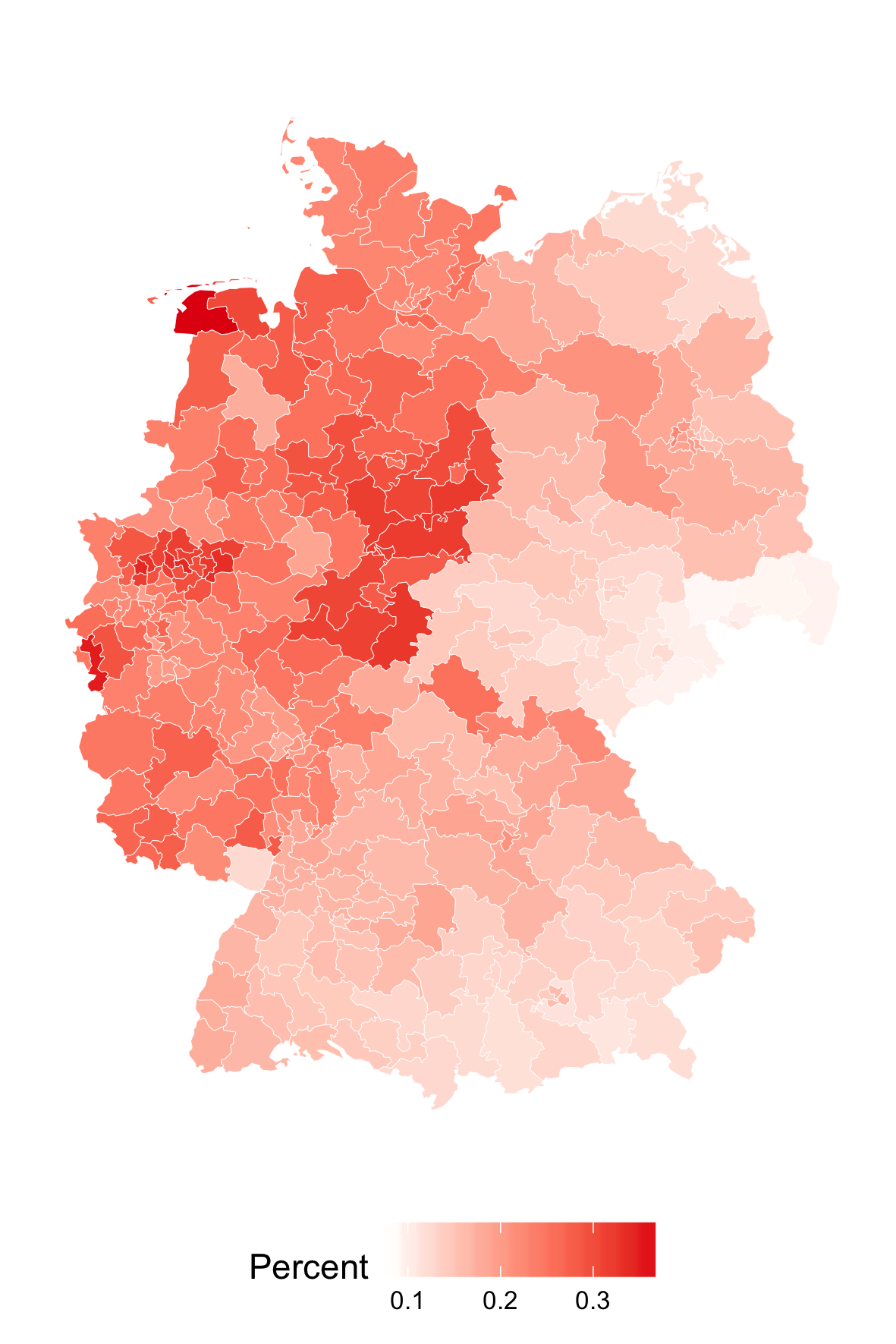

The SPD’s inability to connect with the electorate is greatest in Bavaria and East Germany, as figure 2 shows. In Bavaria, the SPD has traditionally been weak due to the dominance of the CSU, but weakness in East Germany is bad news for the social democrats. In 1998 and 2002 – the only federal elections that the SPD has won after reunification – the SPD was by far the most popular party in East Germany, winning the popular vote in the East by 7.8 and 11.4 percentage points, respectively. In contrast, in 2017, it was relegated to fourth place and only won 14.2 per cent in East Germany. It was unable to address the concerns of East German voters, many of whom are frustrated. Twenty-seven years after re-unification there is still a significant economic gap between West and East Germany and a large part of the population feels left behind.

Figure 2: Vote share for the SPD across Germany in the 2017 federal election

Source: Federal Returning Officer, author’s calculations

The SPD lacks a grand narrative to reconnect with these frustrated voters in East Germany and elsewhere. The party had already shifted to the left in terms of its social and economic policies in the wake of the Great Recession, but it remains hamstrung by inconsistencies within its own programme. Importantly, the SPD has not challenged the orthodox nature of the economic debate in Germany since the early 2000s, when Schröder implemented the Agenda 2010. In 2017, the SPD campaigned under the slogan “time for more justice”, but it offered little beyond technocratic fixes. For all the details that its electoral programme contained, it lacked ideas that could have helped the party to rediscover its own voice. This undermined the ability of the party to reach out to the working class and voters in East Germany.

A third reason for the weakness of the SPD is that it does not have a clear perspective to govern outside a grand coalition. Both in 2005 and in 2013, the SPD could have theoretically formed a left-wing coalition with the Greens and Die Linke, but this coalition was not deemed feasible. SPD politicians are still divided over whether a coalition with Die Linke is desirable, but after the 2017 election such a coalition is not even numerically possible anymore. Instead, the political system has shifted towards the right: whereas the three left-wing parties had a combined majority in the Bundestag in 2013, they now barely hold 40 per cent of the seats. Although the rise of the AfD and the revival of the FPD primarily hurt the CDU/CSU, the SPD also became a victim of the fractionalisation of German politics.

Looking ahead, the SPD’s leadership, party members, and voters are all opposed to joining another grand coalition under Merkel. They rightly fear that this could deal a final blow to the party. However, the SPD cannot simply lick its wounds and lie low until the next election in 2021. Instead, a more fundamental renewal is needed. In the short-run, party leaders will try not to rock the boat until the state elections in Lower Saxony on 15 October. Yet, more dramatic changes in leadership and direction might come afterwards.

The party’s left wing will undoubtedly try to reassert itself and the election of Andrea Nahles as the leader of the parliamentary faction is already a first sign of this realignment within the SPD. This process will help the SPD to become a strong opposition to Merkel’s fourth government, but the party also needs to do some deeper soul-searching. Together with other European social democratic parties, the SPD must develop a new, coherent vision that clearly demonstrates how they remain relevant in the 21st century. Even without the responsibility of government, the SPD’s to-do list over the next four years will be long. Their task is nothing less than to save social democracy.

This post was first published on the EUROPP Blog from the LSE on 28 September 2017