Corona Solidarity

Published:

This post was co-authored with Philipp Genschel and first published by the EUIdeas blog of the European University Institute.

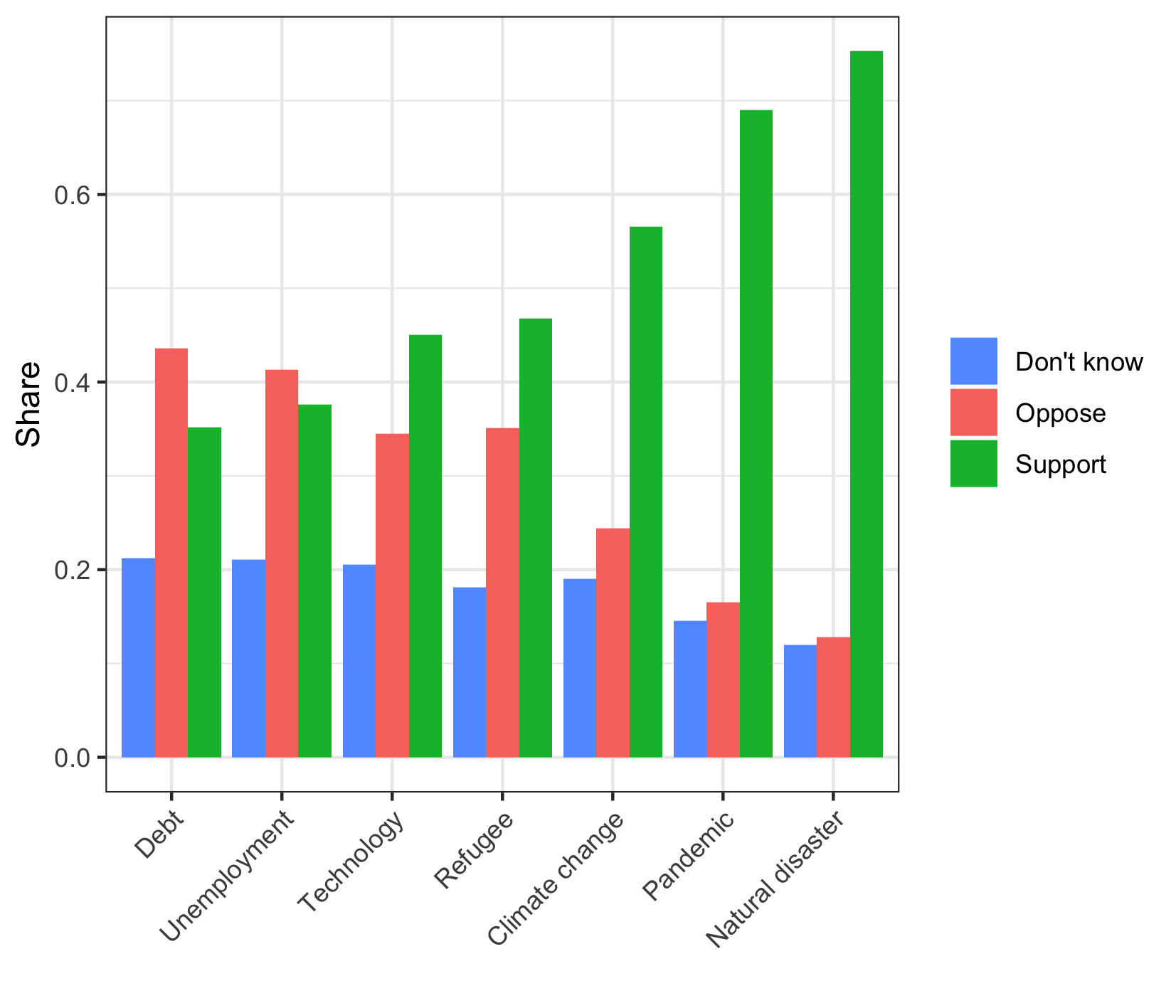

What do Matteo Salvini, Emmanuel Macron, and Angela Merkel have in common? They all call for European solidarity to fight the corona-crisis. Figure 1 shows why: when a pandemic strikes, solidarity is popular with voters.

Figure 1: Support for EU solidarity across different types of crisis

Note: The figure shows the share of different response options to the EUI/YouGov survey question: “Now, imagine another country in the European Union is suffering [CRISIS]. Do you think [COUNTRY] should or should not provide any major help?”

In April 2020, at the height of the European corona-crisis, YouGov conducted a representative survey on public attitudes towards European solidarity on behalf of the EUI. The sample included roughly 22,000 respondents in 13 EU member states and the UK. A key question was whether respondents support or oppose financial assistance to other member states. As Figure 1 shows, the answers vary greatly with the policy issue at stake. While 75 per cent of all respondents support financial help to member states suffering from natural disaster, and 69 per cent support help for pandemic-stricken countries, only 35 per cent support financial assistance to overindebted governments.

Some forms of help come easily

The popularity of pandemic-solidarity is unsurprising. Pandemics, like natural disasters, have exogenous causes. States do not usually bring infectious diseases upon themselves by design. Moral hazard is not an issue. All states are at risk of contagion. Being hit is collective bad luck, making victims easy to empathize with.

If this was all, European solidarity should have emerged quickly and easily during the corona-crisis. Indeed, after some initial glitches, the member states have embarked on various collaborative projects to manage the health emergency: joint procurement and stockpiling of medical equipment, joint repatriation flights of stranded EU citizens, patient transfers from corona-hotspots in France, Italy, and Spain to member states with spare capacity such as Austria, Germany, and Luxembourg.

All this was useful but mostly a sideshow because the real solidarity issue is not health, but fiscal relief.

An economic disaster

The corona-crisis is a major economic disaster. While countries like Germany and the Netherlands can easily borrow large sums of money to respond to the shock, the borrowing capacity of Italy or Spain is constrained by high levels of prior debt.

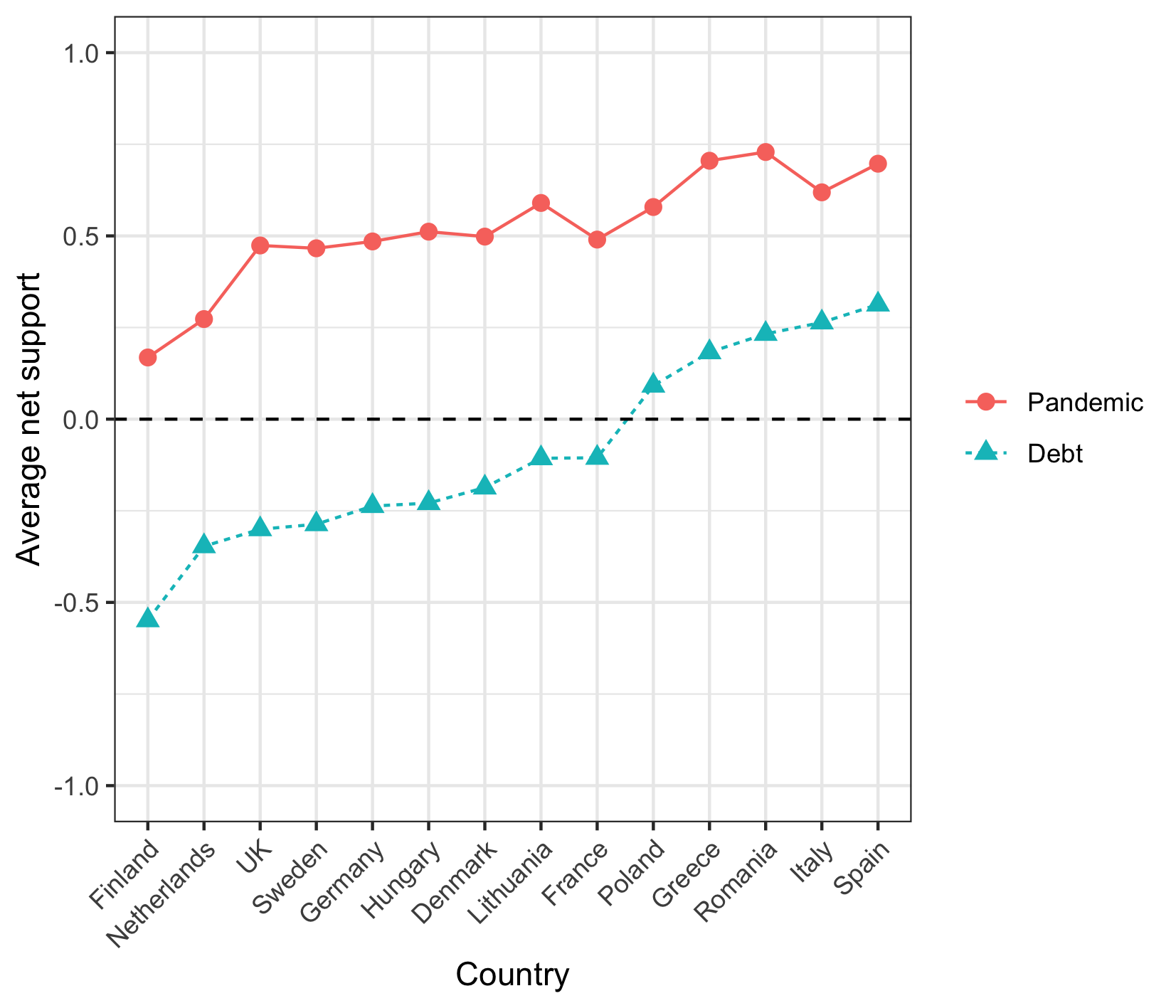

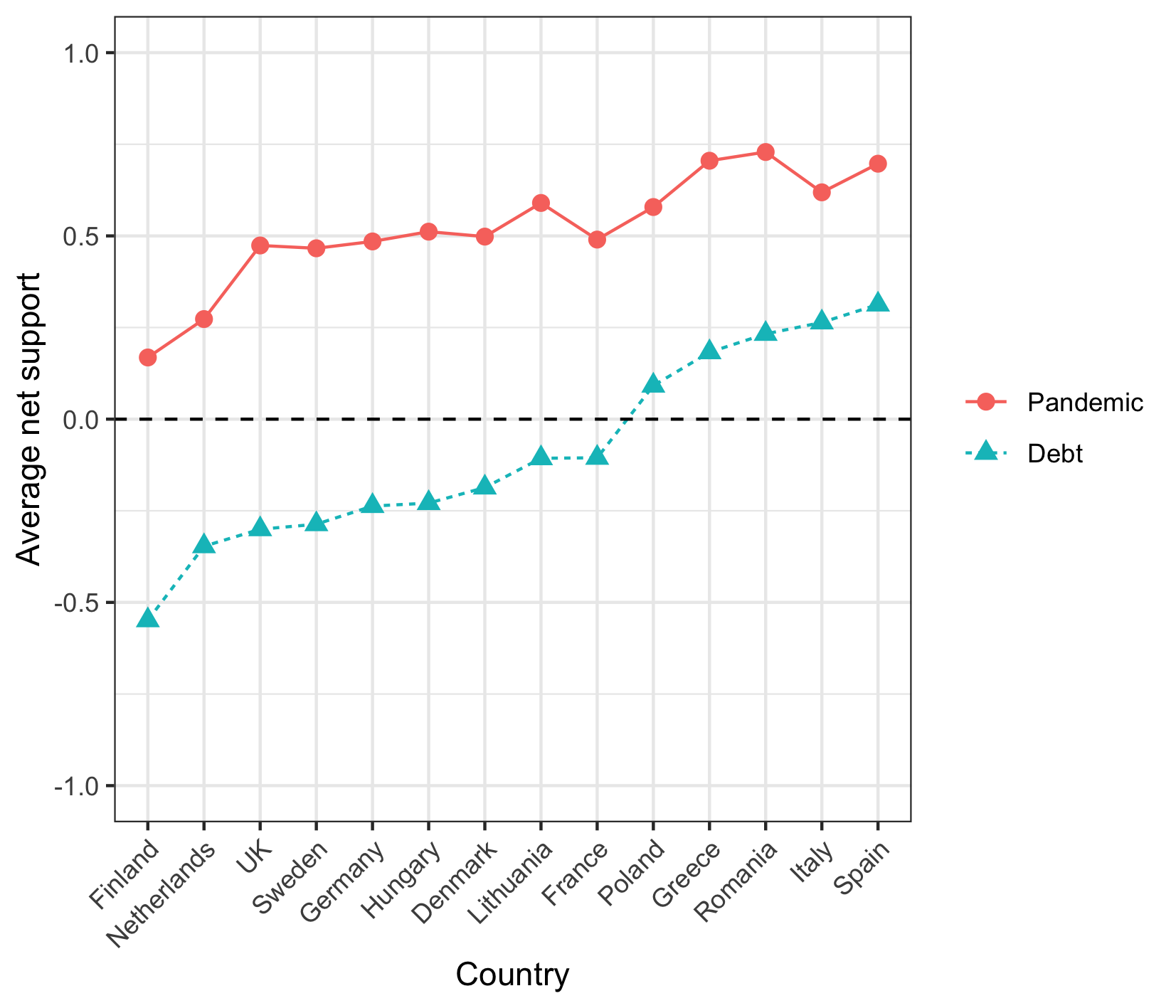

The key question is whether the EU should prop up their fiscal firepower, and how? Through loans or grants? Through the ESM, Coronabonds or the budget? Through “real budgetary transfers” or “fake money”, as Emmanuel Macron put it? Clear-cut answers are made difficult by the peculiar fusion of debt and disease that the corona-crisis brought about. Figure 2 helps to understand why.

Figure 2: Average net support for pandemic-solidarity and debt-solidarity by country

Note: ‘Average net support’ refers to the average of supporters (coded as 1) and opponents (coded as -1) in a given country. For the underlying survey question see figure 1.

As the figure shows, average net support for pandemic-solidarity is high and positive in all member states. Support for debt-solidarity is much lower across all states, and clearly negative in net-contributing states such as Finland, Germany, or the Netherlands.

Little empathy for debt, but not heartlessness

Debt-solidarity is unpopular for all the reasons pandemic-solidarity is popular. High levels of debt are commonly associated with endogenous causes, with negligence, policy mistakes, or structural or institutional deficiencies rather than exogenous shocks and bad luck. Moral hazard is an issue. Insolvency risks are distributed unevenly across states. Net-contributors fear being left stranded with costly and one-sided obligations to subsidize laziness and lack of competitiveness. Empathy is low.

The low, and often negative, support for debt-solidarity accounts for the intensity of intergovernmental conflict over the sharing of the fiscal corona-burden. Yet, the high support for pandemic-solidarity anchors the aspirational benchmark for agreement. Against this benchmark, opposition to fiscal sharing appears petty and mean. When Dutch finance minister Wopke Hoekstra invoked the well-worn trope of moral hazard to justify his resistance to Coronabonds, not only Southern governments reacted with outrage, but also parts of the Dutch public.

The benchmarking effect puts the frugal North on the defensive. This facilitated concessions that would have been unthinkable during the Eurocrisis such as the suspension of the Stability- and Growth Pact or the creation of new loan programs with soft conditionality by the Commission and the ESM.

Whether there is more to come will ultimately depend on two things: how Northern countries manage the cognitive dissonance between pandemic-solidarity and fiscal rectitude; and what Southern countries will ultimately accept as a minimal show of fiscal solidarity.

We focus on two key countries to explore these issues, Germany and Italy. As figure 3 shows, all German parties are conflicted between a desire to help other member states with the pandemic and an aversion to debt mutualization. Variation is limited. Green voters are the only group that supports debt solidarity by a relative majority. All others oppose it by relative or absolute majorities. The likely result is immobilism, uneasy denial, and foot dragging.

Figure 3: Support for pandemic-solidarity and debt-solidary in Germany by party

Note: For the underlying survey question see figure 1.

What next?

Three factors could change the German picture. First, a quick exit from the lockdown and a fading of the health emergency from public memory could reduce the salience of pandemic-solidarity. This would relax cognitive dissonance and facilitate a hardening of Germany’s fiscal stance. A second wave of infections and new lockdowns would have the reverse effect: increased salience of the pandemic perspective and a decreased weight of fiscal considerations.

Second, the judgement of the German Constitutional Court on the ECB’s bond buying programs of 5 May 2020 could push the German government towards more fiscal concessions. It constrains the ECB’s ability to provide fiscal solidarity through the monetary backdoor, thus making it harder for Germany to dodge demands for political decisions on risk and burden sharing. Free-riding on the ECB as solidarity provider of last resort becomes more difficult. A first assessment of the judgement can be found here.

Finally, the German government could override domestic fiscal aversions to protect the coherence and viability of the EU. Whether such a leap is required, depends in large part on Italy. Italy has been particularly hard hit by the coronavirus. Disappointment about Europe’s perceived lack of solidarity was widespread. Support for EU membership dropped significantly. While in April 2019, 54 per cent of Italian respondents to the EUI/YouGov survey still said they would vote to remain in the EU in a hypothetical referendum (25 per cent leave), the remain-vote had decreased to 39 per cent (41 per cent leave) by April 2020. The picture is even more bleak, if we look at voting intentions across Italy’s main parties.

Figure 4: Vote choice in a hypothetical referendum on EU membership in Italy by party

Note: The figure shows the share of different response options to the EUI/YouGov survey question: “If there was a referendum on membership of the European Union, how would you vote?”

As figure 4 shows, the PD is the only large party with consistent support for EU membership. Voters of all other parties favor leaving the EU by large margins. Opposition is highest among Lega-voters, currently the largest Italian party. If Germany wants to firmly re-anchor Italy in the EU, the current M5S-PD coalition is the government to do business with. Presumably, however, this will take more than warm words and fiscal symbolism.

Governments should act while the feeling is high

It is time for Germany and its frugal peers – Austria, Finland, and the Netherlands – to leave their comfort zone. Their economies depend heavily on the Single Market and the Euro. Large majorities of their voters want to keep the EU. If this requires sacrifice, they should better tell them now. Don’t waste the crisis!